"We can no more change the past than live again": Peter Hammill, Taylor Swift and refashioning the fashioned

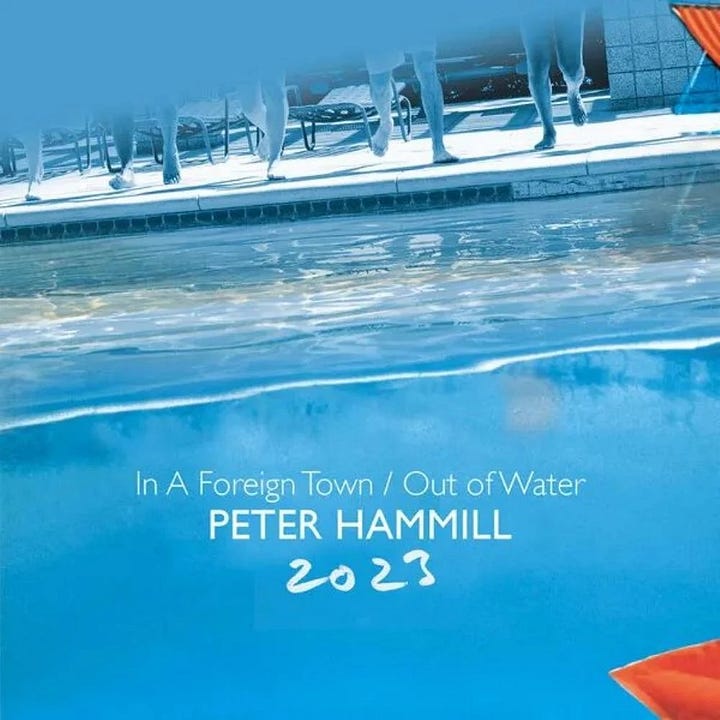

Next July, all being well, my daughter and I will be among the 50,000 people vibing to Taylor Swift’s Eras Tour concert in Zurich. My daughter having informed me that I can’t attend the concert unless I sing along to all the songs, I’ve been making efforts to acquaint myself with Swift’s back catalogue. My newfound interest is timely, since Peter Hammill namechecks Swift in the sleevenotes of his new album, which consists of re-recorded versions of two of his previous albums, In A Foreign Town (1988) and Out of Water (1990).

Both of these albums, along with the excellent live album Room Temperature, were originally released by Enigma Records, an outfit that has long since disappeared into a black hole of corporate mergers and takeovers. That being the case, the question of ownership of the recordings remains murky – a situation that has spurred Hammill on to re-record both albums, thereby laying claim to the songs themselves if not to the original recordings. (What I don’t understand in all of this is how, since Hammill evidently doesn’t own the rights to the original albums, he was able to re-release both of them on his own Fie! label in 1995. It’s complicated, I guess.)

The connection with Swift, of course, is that over the past few years she has also been involved in the process of reclaiming ownership of her earlier albums through re-recording them. In Swift’s case the situation is clearer, since she lost the rights to her first six albums when she left her record company, which was then taken over by a music industry mogul whom she has described as “a manipulative bully”. In order to regain control over those records Swift has since set about re-recording them (she’s done four so far), adding a slew of bonus tracks for good measure.

A question inevitably arises. What is the status of the new versions in the artist’s body of work? Which, if either, should be regarded as the “definitive” versions, and should the new versions be seen as replacing or superseding the originals? In Swift’s case, the bad blood between her and Scooter Braun leaves us in no doubt as to which versions she regards as canon. And yet there’s a mismatch in the new versions between the raw emotion of her lyrics and the voice, made richer and more mature by the intervening years, with which she sings them. If Swift was singing from the heart when she recorded the original versions of albums like Red and 1989, mired as they are in jealousy, trauma and confusion, how can the re-recordings retain the emotional honesty of the originals?

Hammill, for his part, steers clear of assigning definitive status to the new versions of In A Foreign Town and Out of Water, referring to them in the sleevenotes as “emphatically versions for now… while a song is alive no rendition will be absolutely definitive.” Yet in 1999 he had no qualms about describing the re-recording of The Fall of the House of Usher, also brought about by the expiration of rights previously held by a third party, as “the definitive rendition of the opera.” In the end, perhaps all we can say is that both Hammill and Swift would agree with Goethe, who wrote that “refashioning the fashioned, lest it stiffen into iron, is the work of endless vital activity.”

Anyway, most of the responses I’ve read so far to the new Hammill album seem to think that the parallel with Swift is somehow funny, as though it represents an ungodly collision between market-driven pop and pure artistic substance. Those making the comparison into a joke, I venture to say, have probably not listened all that closely to Swift’s music. For one thing, there’s enough artistry and lyrical acuity in the lockdown records Folklore and Evermore to give Hammill fans plenty to chew over. And then there’s “All Too Well”, which I regard as Swift’s greatest artistic achievement to date. The full-length version of this song from the album Red (Taylor’s Version) not only runs a prog-friendly ten minutes and contains several distinct movements, but packs an emotional directness and a profusion of disquieting imagery into its bitter dissection of a break-up such as I’ve rarely heard outside of Hammill’s 1977 masterpiece Over.

As for In A Foreign Town/Out of Water 2023, it’s an update of two records that, to my mind, were in varying states of needing to be updated. Hammill yokes the two records together as, to quote the sleevenotes again, “albums I made for Enigma in the Eighties”; yet although this is strictly speaking correct, there’s a world of difference between the two. Birthed in the febrile political climate of the late 1980s, In A Foreign Town is very much a product of its time, reflecting not only the ongoing misery of the Thatcher years but also seismic global events such as unrest in South Africa and the 1987 stock market crash. Appropriately, there’s a hectic, even overbearing quality to much of the music, dominated as it is by sequencers and drum machines.

Recorded at the tail end of the 1980s but released at the start of the new decade, Out of Water turned away from urban alienation and towards the organic and elemental: earth, air, fire and water. With one or two exceptions the soundworld of the album is quite different from that of In A Foreign Town, with the sequence-driven sound of the earlier record taking a back seat in favour of acoustic and electric guitars, sax and violin. As such, I would say that Out of Water is more of a piece with Roaring Forties and X My Heart, two wonderful albums Hammill would go on to make later in the 1990s, than it is with Foreign Town.

Other than the late Stuart Gordon’s exquisite violin part on “Something About Ysabel’s Dance”, which has rightly been retained from the original recording, Hammill has re-recorded everything from the bottom up for these new versions. In the case of Foreign Town, there’s not a whole lot of variation from the original in terms of instrumentation. Despite the addition of a dense guitar riff here and a squelchy synth pattern there, the LP remains defined by its heavy rhythm tracks and general air of overheated turmoil. The exceptions are “This Book”, which finds a bouncy, oddly attractive groove; “Time to Burn”, Hammill’s grave elegy for Charisma founder Tony Stratton-Smith; and “The Play’s The Thing”, a homage to Shakespeare in which, unless I’m much mistaken, the electric piano of the original is replaced by a grand piano.

The re-recording of Out of Water diverges slightly more from its predecessor, since the original contained elements of saxophone by ex-VdGG man David Jackson and guitar by K Group alumnus John Ellis, which have been replaced by new guitar and keyboard parts played by Hammill himself. The aforementioned “Something About Ysabel’s Dance”, meanwhile, now includes a heated interlude from Charlie Mingus’s “Ysabel’s Table Dance”, which Hammill and Gordon would incorporate into live performances of the song. The sense of air and space that permeated the original survives and indeed flourishes in the new version of the album.

The most important changes to both albums, though, come not in the instrumentation but in the voice, which like Swift’s has deepened and matured with age. Listening to Hammill sing these songs now, more than thirty years after he first recorded them, is profoundly moving at times. If you’re as familiar with the original recorded versions as I am, and have seen Hammill play live as often as I have, you can sense how deeply the years of live performance have inscribed themselves into the cracks and surfaces of these songs. I’m not sure “Peter’s Versions” will ever surpass the originals in my estimation, but they’re still worthy additions to his extensive discography.